High House Chapel – Restoration Report – December 2025

Philip Newbold, Trustee of The Weardale Museum

On 1 September 2025 work re-commenced on site with further repairs and restoration of the Chapel following the award of substantial MEND and HLF funding

The new funding permitted the detailed design of the re-modelling of the Chapel and the associated mechanical and electrical installations

Summer working restrictions imposed by Natural England due to the bats and swifts meant that this work was being carried out in winter weather.

The first element of the restoration was the replacement of the windows in the north and south elevations with new double-glazed, sliding sash units

Work progressed on excavations for the new, insulated ground floor and on the new, timber first floor structure to provide a large area of levelled gallery.

A new access hatch into the roof void was formed to enable repairs to the roof structure to be completed and safe maintenance platforms installed

In early October, scaffolding was erected to the south and east elevations providing access to the south roof and necessitating traffic management

The scaffold allowed a full inspection and repairs to the existing windows on the east elevation and replacement of the vent grill in the roof void

Externally, work continued with the raking out of the old cement mortar in the stonework followed by repairs and re-pointing with lime mortar

It was discovered that the roof structure had sagged over time and needed to be repaired to provide a level base for the installation of 28 solar panels

It was also discovered that the external walls of the Chapel had become distorted at the gable ends so further, unforeseen repairs were required

We are aiming to complete the restoration of the south roof, installation of the solar panels and repointing of the upper walls so that the scaffolding and traffic lights can be removed during the week before Christmas

Back inside the Chapel, the new first floor was completed at the east end and the materials for the rest of the floor are stored at ground floor level

No scaffolding in sight!

A behind the scenes look into Steve’s “Brick This” (Lego) workshop near the banks of the Tyne (sorry, not the Wear).

This photograph features the well- advanced model of High House Chapel and the Manse. When completed, part of the chapel roof will be cut away to permit viewing inside where a

model of John Wesley will be standing in the pulpit.

Partly financed by our National Lottery Heritage Fund award, eight other smaller models will form a trail that depicts favourite artefacts in the museum, the pulpit and communion rail, plus Wesley’s Monument.

Our latest Tapestries

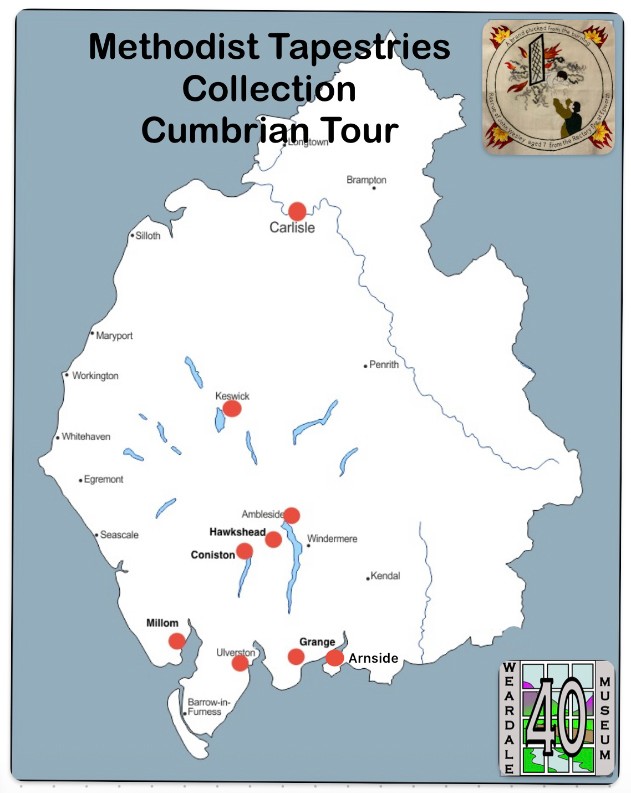

In 2024 we received a request from the Methodist Superintendent Minister in the South Lakes asking if we could organise an exhibition in her Circuit in Cumbria. This would normally be outside our touring range but our Trustee Sue who lives in Keswick gallantly said that she would organise it and do all of the transportation.

From the end of May until the beginning of October 25 of our Tapestry panels were taken on tour to ten different venues including Carlisle Cathedral and were seen by over 5000 people.

We also visited Hexham, Blanchland, Roker and Bishop Auckland as well as giving talks at 6 different venues in the County.

Our programme for 2026 includes Chester-le-Street and Gateshead and we are looking for other venues to visit while our permanent home at High House Chapel is prepared to house the collection.

Over 50 framed Tapestries are now complete with many more in the pipeline. Thank you to our talented embroiderers, to Tracy and her team who mount the embroideries, and to our framer John.

The Annual General Meeting of the Trust will be held on

Monday, 26th January 2026 at 1900

This will be a ZOOM meeting, the link to which is

pwd=T4DUb6O9NPAubTbh1rX9ObRWvpvnZK.1

Meeting ID: 841 5995 3032

Passcode: 385343

The meeting is open for anyone to attend but in the event of a vote, only Friends of the Museum may do so

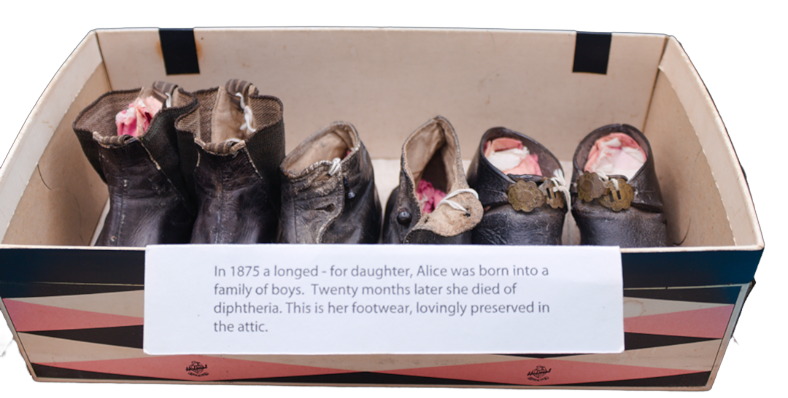

Alice’s Shoes

How were the clogs in our Museum made?

I was in the Museum the other day and standing in the Kitchen, my favourite part of the Museum possibly because it reminds me of my grandparents’ house and especially my Nan’s Kitchen on my cousins’ farm in Devon. When, as I am prone to do, I was looking around and saw the last and the various shoes/clogs that we have and Alice’s Shoes and I began to wonder about their history and how they were made.

The making of wooden clogs with leather uppers and metal protectors (“clog irons”) in the 19th century was a skilled trade combining woodworking, leatherwork, and metalcraft. The process was labour-intensive and required specialist tools and materials sourced from northern England’s forests, tanneries, and ironworks.

Preparing and Shaping the Wooden Soles

Clog soles were carved from green hardwoods, often alder, sycamore, birch, or beech. These woods were chosen for being lightweight yet strong and resistant to water. Woodsmen felled and sawed tree trunks into blocks, which were roughly shaped using a stock knife while still moist and soft (“green”). The blocks were then stacked in pyramids for several months to dry and season while allowing air circulation. Once seasoned, the blocks were sold to master cloggers, who refined the sole’s shape with rasps and short blades and cut a rebate (groove) for the leather upper.

Clogs were designed with a cast, a gentle upward curve at the toe, enabling a rocking motion when walking. In hilly regions such as Weardale, soles were sometimes more curved to help with inclines.

Making and Attaching the Leather Uppers

The uppers were cut from thick leather using metal patterns or templates, a process known as “clicking out” due to the sound the knife made against metal edges. Pieces included the vamp (front), quarters (sides), and heel stiffener, stitched together using waxed hemp thread. Once sewn, the upper was heated, soaked, and stretched tightly over a wooden last to form shape, then tacked to the sole with brass or steel studs.

A narrow leather welt was often nailed around the join between sole and upper for reinforcement, hiding the tacks and preventing moisture seepage. Many cloggers also fitted toe tins—thin steel or brass plates—over the front leather to prevent wear from kneeling.

Adding Metal Clog Irons

Finally, clog irons (also called “caulkers” or “cokers”) were nailed to the bottom of the sole. Typically U-shaped, these strips of steel reinforced the wood at the toe and heel, shielding it from rough surfaces and extending the life of the clog. Ironworks in areas such as Sheffield and Keighley produced these parts, which were custom-fitted by local cloggers. The grooves of the irons were recessed to protect the nail heads from abrasion.

Finishing and Customization

After assembly, clogs were smoothed, polished, and sometimes painted with tar or oil for waterproofing. Some regions developed traditional patterns or painted motifs identifying local makers or villages. The finished clogs were durable, affordable, and ideal for industrial work—making them the preferred footwear for Weardale’s miners, quarrymen, and agricultural labourers throughout the 19th century.

Clog making was a widespread craft across the North and Midlands. Itinerant woodcutters and clog makers supplied finished soles to local craftsmen, who would then attach the leather uppers. In County Durham, including Weardale, clogs were particularly associated with mining, where their thick, insulating soles provided protection against damp floors and falling objects. Workers valued them for their comfort, insulation, and affordability compared to leather boots.

Social and Cultural Role

Clogs were not only utilitarian but also part of regional identity. They featured in clog dancing traditions, with the springy wooden soles producing rhythmic sounds. English clogs differed from fully wooden Dutch clogs (klompen) by offering more comfort and flexibility through their leather uppers. The use of mixed materials—wood, leather, and metal—represents the adaptation of rural craftsmanship to the demands of industrial labour life during the 19th century.

LATE NEWS!

Energy Resilience Fund award

Returning from attending a meeting of the Social Investment Business Foundation’s Investment Committee, Emily, the Architectural Heritage Funds’ Investment Manager had supported us throughout the application process and was present at the London meeting, able to advocate on our behalf.

The Committee awarded us a blended grant and loan facility, thus easing most of our concerns following the loss of expected VAT grants earlier this year. This will enable us to fully complete all our renewable energy measures.

On returning to her Tyneside office, Emily advised:

The Investment Committee were incredibly impressed with your fundraising to date, and noted that this clearly demonstrated that you had provided the level of detail and expertise expected by both the Arts Council and the NLHF. They were also hugely impressed by your proposals and the Passivhaus approach to the adaptations, and could see that the museum was a real asset to the local area and community, particularly demonstrated by the commitment from so many volunteers and clear in your aspirations for the future of the buildings.

FINALLY

We give a huge shout out to the excellent team of Contractors (Coverdale & Hughes) and Sub-Contractors (including NZECO of Wolsingham) who, despite all the challenges from wind, rain and snow, have ensured completion of this first stage of MEND and NLHF funded works to the chapel. They really have gone the extra mile – and will return in January to undertake three further months of restorations.